How To Dig A Threadless - Part A

by Ray Klingensmith

Reprinted from "INSULATORS - Crown Jewels of the Wire", August 1983, page 10

Has it really been that long? Oh my, yes, it has been two years (!) since I've written an article for

C.J. So finally I've decided to get in gear and write a little from time to time

once again. Back when I was writing quite often, a lot of people asked if I'd

put together some info on "how to dig a threadless". Since that time

I've done an awful lot more digging, and with over one half ton of threadless

glass as reward (mostly broken), I feel a little more qualified to write it now!

So, on with a few tips for anyone willing to meet the challenge of findin' an

ole critter.

Most any area in the U.S. and Canada is within a day's drive to a

threadless era telegraph line. Anyone with a little patience and energy can find

a threadless, or at least a part of one, with even the smallest amount of energy

put into it.

Research

This is by far the number one most important factor

involved. You must know where the insulators were used, and when, and it may

also be a good idea to find out what type was used on a particular line. The

importance of doing your homework before your footwork cannot be stressed

enough. You will find the obstacles (rain, snow, cold, heat, annoying insects,

lack of personal physical condition, and plain old not finding something as soon

as expected) all too challenging to keep up the determination it takes to find

something, if you're not sure "it has to be here". What I'm saying is,

if you pursue a particular line, and you're not sure of the original location,

it becomes too easy to give up after some serious effort, because you start to

believe you're not looking in the right place. In finding threadless, you have

to consider the time factor involved from when they were used until now. A lot

of changes, both natural and man-made, have taken place over the years. So, on

with the research.

First off, pick out a line that has a special appeal to you -- one of local historical importance, or perhaps one further away from home

that has better potential, or even more desirable or rare insulators. (I live

fifteen miles from what is one "best insulated" threadless lines in

the country. I've spent less than ten hours of looking on it, and yet have

driven over 3500 miles one way to get to another line!)

Once you've centered

your attention on a line, find out as much as possible about it. Learn when it

was built, to determine what may have been used on it. Talk with local

collectors or diggers to find out what has been found in the area. Next, get

yourself some old history books that give some good general info. For some very

interesting reading I strongly suggest the following: The Telegraph in America

by James D. Reid; Wiring a Continent by Thompson; Old Wires and New Waves by

Harlow; History, Theory & Practice of the Electric Telegraph by Pope. The

first three can be found in some of the larger libraries. If they do not have

them, they will get them for you. In most cases all you will have to pay is a

dollar or two for postage. Both Reid's and Harlow's books have been reprinted

and are presently available for sale. I have several reprinted copies of Pope's

book. Let me know if you want to purchase one. Of the above four, I'd say Reid's

has the most factual info on the company histories. Thompson's book gets more

into a lot of the legal battles, etc., but has much on line locations and

construction. In some cases these books will describe and illustrate the

insulators used on various lines. These books will give you a good deal of

general info, and in some cases give you some detailed info on local material.

Once you've exhausted these books, look a little further into other sources.

Contact local libraries for area history books.

Another good source is

historical societies and museums. Sometimes they will be of little help, but

many times they can be of great help. You might want to check early newspapers

of the time the line was completed. In many cases the old local newspaper

offices have a copy of most or all of the papers they've ever printed. If you

can determine when the line was put into operation, there is a good chance there

was a feature article on it. Old local photos of the area are also of great

help. Once again, contact historical societies, libraries, universities,

colleges, archives or other government agencies. The photos will be of great

value in determining what side of the road or railroad the line was originally

on. In some cases they were relocated on the opposite side when rebuilt. So get

as early a photo as possible. When you look through an index at the above

mentioned agencies, look under "telegraph" first, but other listings

might be communications, or possibly the name of the company that built the line

(Western Union, U.S. Tel. Co., etc.). There might also be material listed under

the contractor who built the line, or the man in charge of construction of a

certain section. As an example, James Gamble or Western Union Tel. Co. could

both be listings when searching for info on the 1861 Transcontinental line. You

might also want to check with local court houses for line right of way, leases

or other legal material on a line.

And last but not least, talk with the old

timers in the area. Explain to them in detail all you know about the line. It

might help to show them a broken sample or photo of what you are looking for.

Listen carefully to what they tell you. In most cases they will be very

interested and help you all they can. But let's be logical. Most threadless

lines have been gone for one hundred years or more. These people will be very

sincere and believe they know the line you are talking about. In reality, many

times they are referring to a line that is, yes, very old, but not the same one

you are looking for. But there have been instances the old timers have sent me

straight to a location where threadless were used. One ninety year old gentleman

stands out in my mind. He was a wise old timer, full of energy, and had a

perfect memory. He pointed on my map, referred to the lake shown on it (That's

"Thank You Lake", Cecil.), and described how the old 1866 line ran

about eighty yards from its banks. He hadn't been there for seventy-two years,

and even though the line wasn't standing back when he was there, he still knew

it was there at one time. So off I went, hiking into the bush probably a mile

and a half from the new paved highway. After a good, long refreshing hike I

arrived at "his location". Well, he was wrong. This very remote place

didn't show any sign of the old line, not where he said. It wasn't eighty yards

from the lake, it was eighty-five yards! Yes, it was there!

Speaking of maps,

they will be one of your best friends in searching most lines. Try to get an

early map showing the route of the telegraph line. Pay particular attention to

the location of the line as compared to lakes, rivers or other land features.

These old maps are usually fairly accurate. By using a modern day map, you can

compare the two and pinpoint approximate location of the line, and see access

roads, obstacles, etc. There are very few early telegraph maps available, but

some do exist. Do your best to find one, and if you can't, at least pencil in on

a new map the town names you know the line went through. If you can find

detailed info on a location or two, it will at least be a start. As far as maps

are concerned, a good road map of an area will do the job in the more populated

areas of the country. However, if you plan a trip into a remote or wilderness

area, don't hesitate to invest in some good topographic maps. These will show

watercourses, roads, changes in elevation, etc. These are of great help in an

area where land features are the only clue as to where you are. In some cases

they could save your life. (As an example, I spent over eighty dollars on new

topo maps of a route of one line, and, believe me, after getting to the

location, I'd have gladly given twenty times the price paid for some of them.

There are times you need them -- badly!) Assuming you've now done your homework and

know what you are lookin' for, let's get to the next step.

|

Large Image (158 Kb)

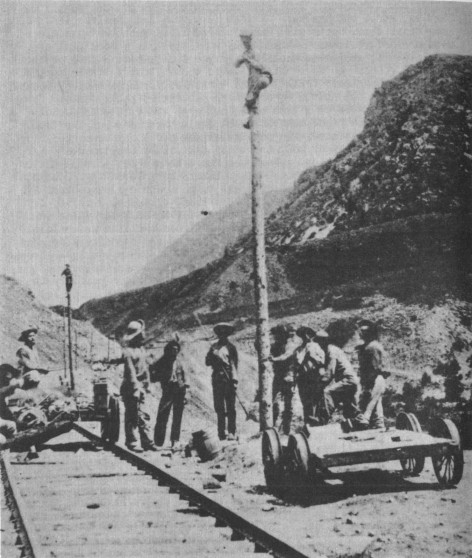

The telegraph

crew hard at work in 1869 building the UPRR line through Weber Canyon, Utah. The

man kneeling, at the extreme left of photo, is swinging a hammer, driving the

spikes through a side bracket and into the pole. The mounted bracket is complete

with insulator! Photos similar to these could be very useful in pin pointing

the exact location of poles in your insulator hunting today, if it was on a line

that hasn't been disturbed over the years. Un fortunately, this particular area

has seen many changes, including a four lane highway through the canyon.

Photo

courtesy of Utah State Historical society. |

Equipment

The type of equipment

needed for a hunt will largely depend on where you are going to look and how far

from home you will be looking. On the shorter trips, all you will need will be

the basic tools. I personally like to have along the four basics. First, my

"digger". (See figure A below.) I like to use this particular type of

tool because one can do good quick work and at the same time, with a little

common sense and care, not smash what you are looking for when you eventually

find it. These "rakes" come with teeth of various thicknesses and

lengths. Don't go out and buy one of the smaller lightweight ones. They just

don't hold up, and the teeth will bend or break after a short time of use. At

the same time don't get a super heavy duty unit, either, as it can wear you out.

The medium size, as shown, is heavy enough to handle the rocks and roots.

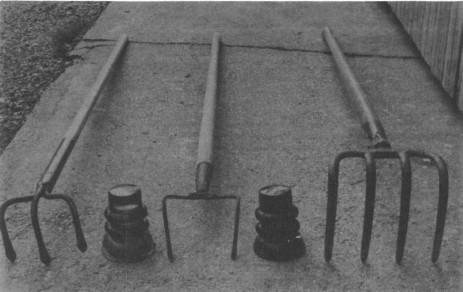

Figure A. The #1

tool of the trade. These rakes are available in various sizes. The one at left

will serve the purpose well in most places. The one at center is the type you do

not want to buy. It simply isn't heavy enough, and will, after a short period of

use, end up looking like this one, in want of its two front teeth. The one at

right, although it appears large, seems to do a good job after one gets

accustomed to working with it. |

Your

number two tool will be some type of shovel or spade. There will be times your

digger just won't do the job, and a shovel will be needed. This is especially

true in hard soil, heavily rooted, and rocky areas.

Number three tool is your

"dooger retriever" (Right, Skip?). You should have some type of small

tool (See figure B above.) with one long prong to work in the tight places. such

as under trees. These don't take up much room, and there are times you can't use

anything else.

Number four "tool of the trade" is a small saw, which

can be of great help in areas where trees or small underbrush get in your way.

It's amazing how much more enthusiastic you become if the area is cleared of

obstacles. A lot of roots that otherwise slow you to a crawl can be removed for

easy digging. Don't forget to pack a saw along.

Depending on where you are

looking, another very valuable tool is a metal detector. Most lines, whether

cross country, along a railroad or road, will have some form of metal relics to

be found from the old line. These will be mostly old line wire, tie wires, or

the old square spikes used to fasten the brackets to the pole. If you can locate

a line that made use of metal brackets (See figure C.) then you are really in

business. The only problem with this method of searching is the over abundance

of recent metal "junk" found in unbelievable quantity in the same area

where the line was located. But be patient. The tie wires and spikes are almost

always there. If you can stand the disappointment of digging a lot of false

alarms, the end result will be some old metal. Make sure you have an extra set

of batteries (or two) in case your old ones die on you. Also, the speakers in

these gadgets are very sensitive to moisture. One drop of rain in them and

fizzle -- no sound. If you are a thousand miles from the nearest detector dealer,

and your speaker goes fizzle, you can use ear phones which are available in most

locations. That's what one Iowa insulator hunter ended up doing after a little

rain shower put his machine out of service. After a day and a half of crawling

around under the pine trees on hands and knees, with his ear to the ground

listening for "Chester chatter", he decided it just wasn't producing

any glass! Thank God for Radio Shack. So, play it safe and cover your detector

with a plastic bag or something similar when it's wet outside.

Other equipment,

depending on where you are looking, includes compass, first aid kit, snake bite

kit, extra food and clothing, and a lighter. The compass is very important if

you are in a more remote area. For the "wilderness trips" I'd also

suggest packing in a lot more food and water than you think you will need. You

never know when an emergency will arise. Also, take enough extra clothing along

that you could survive a cold night without shelter should you become injured. A

small waterproof jacket is very sensible. All your extras will easily fit into a

small lightweight backpack. A backpack is better than something carried in the

hands, as it will be less tiring and will leave the hands free to maneuver.

Besides, if you find any insulators, you will need a place to put them to carry

them out. Don't forget a little wrapping material to protect your finds. Old

socks work real well, as does newspaper. Good old "T.P." comes in

handy for wrapping, as well as other things. (Ha, ha.) Don't forget it!

Another

tool you can use, with which I've had no experience, is a "poker".

(Contact the Plunketts for all the secrets of this method.) In the swampy areas

you can use a three or four tined fork. Make sure the tines are fairly close

together and rather long. (You might want to cut down a six or eight tine fork,

as the "teeth" are usually closer together than on one originally made

with fewer tines. Using this tool you can poke in the old bog until you

"feel" it hit glass. An old pro can tell in a instant the difference

between glass and a stone or rock. Glass is much smoother and has a different

feel and sound than stone. It takes some practice, but after awhile you can get

on to the method. Like I said, this method works best in swampy areas where it

can be very difficult digging.

Paint your digging tools a bright orange or

yellow. It will save an awful lot of time hunting for them after you lay them

down, and a few minutes later decide you've lost track of 'em.

|